Martinelli’s extradition and Noriega’s

by Eric Jackson

United States Magistrate Judge

The readers should know that precedent plays a much larger role in the Anglo-American Common Law systems of justice than it does in the Civil Code systems that derive from Roman Law via the Napoleonic Code. US law, with some exceptions in Louisiana and the US colony of Puerto Rico, is of the Common Law tradition, deriving from a legal system developed case by case in an England with no written constitution as such. Panamanian law, of the Civil Code lineage, takes little heed of previous cases and instead concentrates on the letter of written laws, informed by certain maxims and rules of interpretation.

Extradition, that’s a matter of international law, in the case of one Ricardo Martinelli Berrocal an intersection of Common Law and Civil Code jurisdictions, governed above all by written treaties but also by the customary law of nations. One of the important customary values of international law and relations is reciprocity.

Can we talk of reciprocity between the United States and a nation with a population barely one percent the size of its own? Can we talk about reciprocity between a country whose military forces operate on Panamanian soil and seas, and in our air space, with notwithstanding agreements formally mutual there is no such Panamanian presence in the United States? Is any such discussion relevant given a narcissistic rich kid bully who is clueless to the world of diplomacy occupying the White House?

Although Mr. Trump may be offended at the suggestion that it may be so, there are adults on the scene, in the other branches of government and in the bureaucracy of his own, who matter in the American scheme of things. Judges — even those with surnames like Torres — make decisions that matter, frequently without regard to what presidents may wish them to do. In any case, as the US State Department approved the move toward extraditing Martinelli to Panama, it would probably be erroneous to presume that Trump doesn’t want to rid the United States of the former Panamanian president. As much as reciprocity appears not to have any role in the motives of Mr. Trump’s personal behavior, he probably has his other reasons in the extradition case at hand.

For Judge Edwin G. Torres, the federal magistrate presiding over Martinelli’s extradition trial in a Miami courtroom, it should matter. Reciprocity is both a form of precedent and principle of international law. To the Republic of Panama, notwithstanding the rampant suppression, ignorance and falsification of our history, reciprocity is a basic requirement of national dignity.

The precedent is that US courts don’t care how a defendant is brought before them. US authorities have kidnapped people, in plain violation of the laws of other countries, to snatch drug defendants from their foreign refuges and bring them before US courts. US authorities have used perjury before foreign courts to get people extradited to the United States. Not the court’s concern has always been the response to defendants brought in by such and similar means.

At the moment there is speculation that, as arguably in the case of Noriega’s extradition from France, Judge Torres may condition a Martinelli extradition on a stipulation that there would be no trial for our former president save on the wiretapping charges on which the extradition request is premised. But that uncontested extradition from France was had under Franco-Panamanian treaties and customs. Noriega’s transfer back to here included a controversial and later moot agreement that the former strongman would serve an outstanding sentence and face then-outstanding charges, but not face trial for other crimes.

For Martinelli, if such conditions were imposed and respected, it could mean no trial on the illegal pardon not only for cops shooting innocent people but also for them planting false evidence on their victims. No further investigation of the computer crimes of which the list of 150 “most hated” people whose phone calls and email were monitored and whose cell phones were turned into room bugs were only a part. No trial for all of the overpriced public contracts with kickbacks. No Odebrecht cases. No further investigation of the Vernon Ramos disappearance if evidence points to the involvement of one of its principal beneficiaries, Ricardo Martinelli Berrocal. None of that. None of the other cases pending before the high court, none of the cases which ought to be brought. Or so the speculation goes.

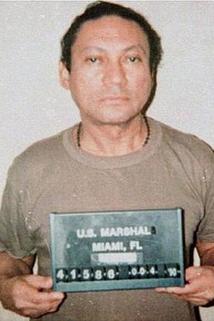

But Manuel Antonio Noriega was brought to the United States from Panama in clear violation of the Panamanian constitution, which bars the extradition of citizens to other countries. We can argue about whether that’s a good law, but there it is, and there it long has been.

The reciprocity, and customary practices, which matter in this case are the standards that US courts have applied to Panamanians brought before them by irregular means. In those cases there have been no limits other than facts, US laws and American public policies on the matters for which the defendants might be investigated or tried. Panama never received any assurances.

Were Judge Torres to take a wise long view at US relations with the rest of the world, he would turn down any suggestion that Martinelli’s extradition should bar investigation or prosecution for any of his many other serious crimes. For him to favor Martinelli with any such extraterritorial court-imposed limitation would violate the bedrock US principle of equal justice under the law.

But what if the court in Miami does extradite Martinelli with such restrictions on his further prosecution? Then Panama should assert reciprocity. Under that principle it should not matter how Martinelli comes into custody here — once he is in custody here, he is subject to full Panamanian jurisdiction in all cases in which it can be reasonably shown that he probably violated Panamanian laws. “But it’s illegal — under the US court ruling…” would merit the reciprocal response that such objections are not the court’s concern.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story confused Federal Magistrate Edwin G. Torres, a Bolivian-born judge in Miami, with Judge Edwin Torres, a New York judge of Puerto Rican ancestry and author of “Carlito’s Way.”

~ ~ ~

These announcements are interactive. Click on them for more information.