This republic of ours

a Panagringo perspective by Eric Jackson, cédula 3-721-1318

Formally, Panama became an independent republic on this day back in 1903. Before then it was something of a distinct society, both within the shrinking Colombia that Simón Bolívar established but could not manage and before that in the Spanish Empire as part of the haphazardly created Viceroyalty of New Granada.

The de facto realities are more complex. On the state level, and on personal levels, there are things that an awful lot of Panamanians would rather deny. Panama’s independence is and always has been an ongoing process of many levels of decolonization, one that has met resistance every step of the way. The initial skirmishes were led by Quibian and Christopher Columbus respectively. The battle is not over.

The November 3, 1903 separation from Colombia was an almost bloodless coup by a conspiracy of three forces. There was a New York corporation with significant French shareholders, the Panama Railroad Company, which held the residue of the French canal concession and stood to lose a lot of money if nothing drastic happened before that contract expired on December 31, 1904 as scheduled. There was the local branch of Colombia’s Conservative Party, a minority force on the isthmus albeit because of Liberal military errors in firm control of Panama City and the railroad route since the outset of the 1899-1902 Thousand Day War. Then there were the Americans, Teddy Roosevelt and the forces under his command.

By bribery, treachery and a carefully timed set of US naval moves the third great secession from Bolívar’s Gran Colombia was pulled off. (Venezuela and Ecuador left earlier, and centrifugal forces still support local warlords in modern Colombia.) Exhausted by Colombia’s never-ending wars and exasperated by the clueless and aloof Bogota political scene, even the Liberals were willing to accept it, provided that the old merchants’ dream of a canal, a work in progress begun under French sponsorship, would become something real.

The construction of Panama as an independent republic? That began to take force after Roosevelt left the White House and the political protection for the unpopular Conservatives went with him. But actually, there was evidence of it right from the start. November 4 is Flag Day, when something perhaps too similar to the US flag was unveiled in lieu of a different knockoff provided the the Wall Street law firm and Washington lobbyists for the Panama Railroad Company. Also ditched at the time was the draft of a declaration of independence that came with those consultants’ revolution kit.

But it was Belisario Porras, the Liberal leader who became legally Panamanian by popular demand after an initial Conservative ban, who came to lead Panama toward being a nation in its own right. He never much liked the arrangement with the Americans that came with the separation from Colombia, but in his time made small incremental changes on parts of that which he could change and avoided confrontations over the rest. Mainly he began to build the institutions that distinguished the new Panama as a sovereign nation rather than a wayward department of Colombia.

The political institutions? The Conservative Party died out on Porras’s shift, not by any process of harsh repression but because it just didn’t represent anything particularly relevant to the great majority of Panamanians.

But weren’t there Panamanians with different ideas and temperaments than those of Belisario Porras? Indeed there were – and these differences were fought out within the Liberal Party and later among its splinters. It was to be expected. The Liberals here were starkly divided long before the days of Porras. The old notion of “They have an exclusive deal with this choice sponsor, so to stay in the game I’ll go looking for another sponsor” kept the colonial mentality going in the minds of many Panamanians and through them in the new country’s institutional expressions.

Into the 20s vestiges of the protectorate remained strong. Panama looked to the Americans to solve a border dispute with Costa Rica and their relations with Gunas who did not care to assimilate themselves out of existence and launched a bloody race war over that. US maraines suppressed a rent strike in which were involved a lot of West Indian former canal construction workes and Spanish and Italian anarchists whom later generations of radicals forgot but were important founders of the Panamanian left.

Then a liberal faction that fashioned itself after the Ku Klux Klan, advanced racial definitions of who and what is Panamanian and thought very highly of the then emergent European fascist leaders split away. The organizational heir to that schism is today’s Panameñista Party.

Observing all this while stationed in Panama was an up-and-coming US Army officer, one Dwight D. Eisenhower.

As US entry into World War II approached and German u-boats prowled about the Caribbean Sea, Washington could not abide the Nazi symp Arnulfo Arias in the Panamanian presidency. It was all bloodlessly and “constitutionally” arranged in October of 1941 when Arias took a private trip to Cuba without notifying the legislature. The cops enforced the coup, and rising through the police ranks to become the real power even before he became the formal commander, then later becoming president until his assassination, was Colonel José Antonio Remón Cantera. Remón was careful in his relations with the Americans as Arias was not, and also had an understanding counterpart in US President Eisenhower. They call it Torrijismo after General Omar Torrijos, but Remón’s moderately social reforming militarism, also an offshoot of the Liberal tradition, gave rise to today’s Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD).

The left insisted, most Panamanians, who were not of the left, agreed with them and the Pentagon understood. The Canal Zone ended, the US military bases and US canal management were phased out, and Panama became whole in a more formal sense.

However, not all that completely. That special deal with a foreign sponsor, that underestimating of self, that craving to get rich without producing anything, that urge to protect self or family or social strata by denigrating “others” in our midst, the attraction of kleptocracy — these ways of thinking and their standard bearers are Panama’s present-day foes as we strive to perfect our incomplete project of national independence.

This weekend we celebrate our nation. People come from afar to join the party. Small and imperfect as it may be, Panama is wonderful. We celebrate that as we look ahead to better things.

~ ~ ~

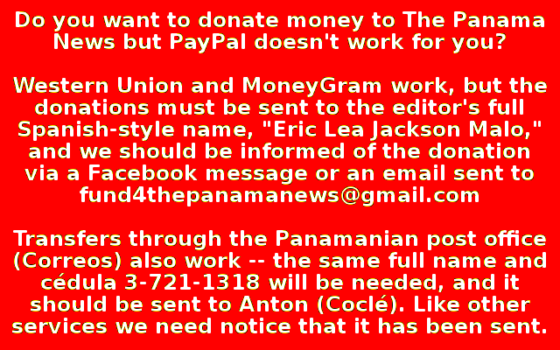

These announcements are interactive. Click on them for more information.