Dr. Luis Francisco Sucre, the new health minister. He steps up from the vice minister’s post. He’s the who, given his predecessor’s embarrassing conflict of interest, imposed the fines on the PRD and Jimmy’s restaurant after a controversial meeting of the party’s electoral committee in violation of curfew rules. He’s a Panamanian and Argentine educated physician specializing in occupational health, who has also serves as the director of the SINAPROC disaster relief agency. Sucre is from a family with extensive political ties and a power base in Panama City’s corregimiento of Juan Diaz. His brother Javier is a member of the National Assembly. MINSA photo.

Dark days with rays of hope

by Eric Jackson

Things are in disarray.

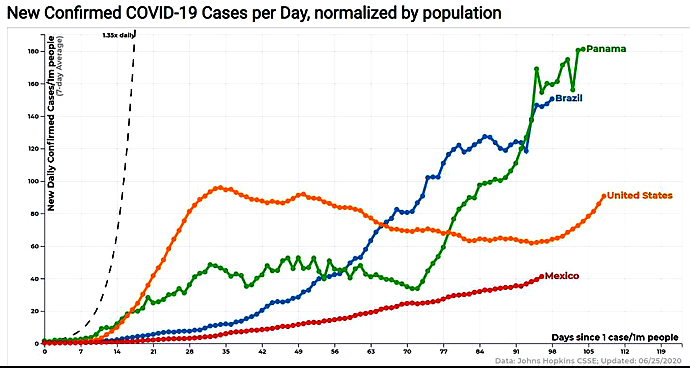

For the past week, every day Panama’s pandemic death toll has been in double digits. Lately the number of new infections reported daily has been topping 1,000.

The nation’s intensive care ward capacity is overflowed. The 90-bed obstetrics and newborns ward at Irma de Lourdes Tzanetato Hospital is no longer used for delivering babies, but to treat adult COVID-19 patients. At Seguro Social’s flagship Arnulfo Arias Hospital Complex, they tested patients in the cardiology and hematology wards, and more than half of the patients in those facilities were found to be infected with the coronavirus and had to be transferred to ward dedicated to those who are infected.

From early on, people on the front line have been obviously vulnerable. Doctors, nurses and orderlies at the nation’s health care facilities are known among those who have become infected, even if them government invents one excuse after another to hide the numbers. It’s to the point where we now see street protests by members of the health care workers’ unions.

So should these protests be broken up by police? It turns out that a lot of law enforcement officers – the number also unspecified by the government but very real according to unofficial anecdotes and terse official death notices – have become infected. In at least one case, the cops staffing a checkpoint on the entrance to one upscale expatriate enclave turned out to be themselves sick with the virus they were there to exclude, and spreading it into the community that they were sent to protect.

People who really ought to be hospitalized for conditions that have nothing to do with COVID-19 are being shunted to other facilities or sent home because the hospitals where they would ordinarily go are not entirely dedicated to those infected with the coronavirus. The epidemic’s full death toll will be understated so long as this condition exists because those whose demises are proximately caused by the unavailability of services due to the hospital overflows will not be counted as infection-related.

Late June figures, necessarily imprecise for lack of universal random testing but with Johns Hopkins statisticians taking the deficiencies into account. What we see, in effect, is the collapse of Panama’s early quarantine measures. Numbers from Johns Hopkins, chart taken from JulieAnn Blam’s Facebook page.

So, who is to blame and what is to be done?

By some ways of thinking, the thing to do is to shake up the team and assign blame. The first part of which President Cortizo has partially done, the second part of which he has mostly left to others.

The most immediate failure has been widespread disobedience of the president’s health decrees. The most massive concentrations of this phenomenon have been in poor areas where most of the people who work do so informally so long have been ignored by the government – except to periodically drive them out of places – and whose existence is not recognized by the government. These people were excluded from the government’s food relief program, headed by Vice President Carrillo, who came to that post from his job as a banker. One of the few concessions to the economic realities of the poor was at the outset to exclude Colon and San Miguelito from the economic team’s requirement that people’s existence be officially recognized in order to receive such food assistance as they were offering. Originally it was $80 per month per household, since raised to $100.

Those left out of work who had no union contracts, tended to be similarly unrecognized. Those with labor contracts but belonging to organizations with which the PRD has off and on been at war for decades – most notably the SUNTRACS construction workers’ union – frequently found themselves excluded from the program for this or that alleged glitch.

Cortizo and his economic team deliberately made a lot of poor folks go hungry, figuring that the police would handle the problems that it created. Mostly the response was not to riot in the streets or loot little grocery stores – although there has been some of that – but to disobey quarantines and curfews and go out in search of ways to make money and obtain food. A lot of people in places like Arraijan and some of Panama City’s poorer enclaves did that, became infected, and spread the virus in their overcrowded households and densely populated neighborhoods.

Leave the insufferable cultural, educational, social and racial theories about poor people in Panama to haughty rabiblancos and to clueless expats informed mainly by prejudices they brought here with them. However, these notions aren’t just about those who scrape by in ways that they generally can’t imagine. The generally privileged castes also have some odd theories about themselves.

A Jewish wedding in Paitilla, a wealthy Evangelical preacher working the streets of Colon, anti-masker gringos in Coronado, politicians who initially called the epidemic a big hoax and made a point of defying the health measures, a celebrity who worked connections to get a special pass, thousands of mostly upscale people who got “humanitarian” passes for weekend commutes from the city to the beach that unconnected people can’t get – the instances have been variously flaunted or hidden. There has been this aristocratic presumption of immunity. However, members of the political caste and their families have been getting sick. So have people in expensive homes in the beach and mountain communities. It’s not like in the densely populated barrios of the poor, but the contagion is out and about among those who had fancied themselves specially protected.

And then the ruling PRD’s deputies, party president and members of the organization’s elections committee defied restaurant closure decrees and time and place of circulation rules to meet at Jimmy’s, a good restaurant near ATLAPA. The occasion was to choose their slate to lead the National Assembly for the 2020 – 2021 legislative year. Health Minister Rosario Turner, one of the elections committee members, signed the call for that meeting. A journalist from outside the mainstream and some political independents found out about the meeting and showed up outside to protest. Shall we more properly say that the demonstrators were mostly there to point out the hypocrisy and not to defend the health measures that they also were violating?

Health Minister Rosario Turner took the fall after the embarrassment at Jimmy’s. She had been getting vilified as this horrible dictator by many of those expats and Panamanians who had opposed and still oppose the health decrees. Nito Cortizo did not consult with other PRD leaders before dismissing her. Afterward, mostly outside of the president’s party, a number of people rose to Dr. Turner’s defense. Here it is the University of Panama’s rector. Several prominent women saw the president’s cabinet changes as a matter of women losing their jobs for a grim situation that was largely created by errors committed by the men in charge of Panama’s economic response to the pandemic. From the rector’s Twitter feed.

The shuffle

On the afternoon of June 24 Nito made his cabinet moves. The economic team, led by Vice President and Minister of the Presidency José Gabriel Carrizo and including Minister of Public Works Rafael Sabonge – the latter much criticized for some overpriced purchases for the new modular hospital in Albrook and irregular procedures and lack of transparency that went with them – remains in place. Gone from the cabinet are three women, replaced by two men and a woman.

By some accounts it was the removal of a faction that questioned the economic team, the pediatrician health minister Dr. Turner and Social Development Minister Markova Concepción, the latter sent to New York to be Panama’s ambassador at the United Nations. By any measure Cortizo turned to influential old PRD families. Turner was replaced by the vice minister, Luis Francisco Sucre, whose family more or less dominates the Panama City corregimiento of Juan Diaz as their fiefdom. The new health minister’s brother Javier is a deputy in the current legislature. His sister Imelda runs the Juan Diaz junta comunal. Javier’s suplente is Omar Castillo, the son of former PRD legislator Elías Castillo and brother of the new Minister of Social Development, now ambassador Conceptción’s replacement María Inés Castillo. Replacing Minister of Housing and Land Management Inés Samudio is former legislator Rogelio Paredes, whose father, the late Rigoberto Paredes, was a key civilian apparatchik for the Torrijos and then Noriega military dictatorship of the 1970s and 1980s. Rogelio Paredes was promoted from the vice minister’s post, which he also held in the 1994-1999 Pérez Balladares administration.

The old guard retrenching to carry on with unpopular policies? An unpopular president who was elected by just barely more than a third of the electorate in the first place approaching the end of the first year of his five-year term with the opposition smelling blood in the water and disinclined to lend him a hand?

The cabinet shift, however, was not the only personnel change. A new presidential consultative committee, nominated by Dr. Sucre, was creaated to include former health ministers Jorge Medrano, Francisco Sánchez Cárdenas and Camilo Alleyne; Seguro Social director Enrique Lau, minister without portfolio and presidential health advisor Eyra Ruíz and the dean of the University of Panama medical faculty, Enrique Mendoza. These folks will advise the president on broad strategic matters, including which areas of the country merit special concern at any given moment and the pace of businesses and activities reopening, or closing again after openings that have not gone well.

At the request of physicians both on and off the committee, the Ministry of Health’s COVID-19 crisis advisory committee was dissolved in order to be reorganized. Most of all of its members will still advise the ministry, but on smaller bodies dedicated to specific tasks such as tracing the contacts of people who test positive, communicating health information to the public, investigating palliative medicines and possible cures or vaccines, developing unified protocols for patient care, and community attention outside of the hospitals.

A few days later, as the flood of new cases began to overwhelm the nation’s largest hospitals, Sucre and Lau formed the Inter-Hospital Control Center to work out a practical division of labor among the nation’s health care facilities. The word “permanent” was used in the announcement. It may well be that the old divisions between the Social Security Fund’s hospitals and those of the Ministry of Health, and within those institutions, will never reappear as they were. Given the magnitude of the crisis, we also don’t know if the nation’s private hospitals will be drafted into a new scheme.

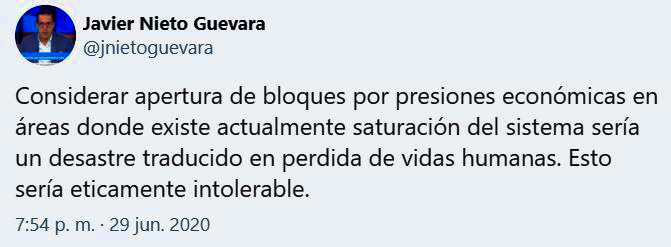

The conflicts between medical advice and business pressures appear to be ongoing in the Cortizo administration as well as in society as a whole after the cabinet shuffle. From Dr. Nieto’s Twitter feed.

Next with the economy?

As the first known COVID-19 cases in Panama came to light this past March, it was easy enough to see that no matter how well or poorly the outbreak was to be controlled, Panama was in for a prolonged economic disruption.

At the center of our economy is the role of transportation and commercial crossroads. Yes, the Panama Canal, but also the seaports that have grown up beside it, and also the regional import/export wholesaling and warehousing businesses in the Colon and Howard free zones. Also the railroad moving containers between the ports and free zones. Also the major air hub of the Americas at Tocumen. Lock these down and the economy locks down.

Keep these running full blast? First of all that could not really happen, given nearly worldwide air travel restrictions and a precipitous decline in global maritime shipping. Moreover, carrying on in the old ways would open our “doors” – bigger, busier and more numerous per capita than those of any of our neighbors – would open us to a free flow of infection to and from the four corners of the Earth. If we were dumb enough to try that, then other countries would have closed their ports to ships coming out of the Panama Canal. We had to slow down, for air travel to nearly shut down. So forget tourism for the duration, and to a great extent also forget commerce.

Also as the quarantine measures were being imposed in March, the Cortizo administration was issuing a third tranche of bonds, part of an aggregate $5.8 billion in borrowing to meet what the president characterized as unpaid and unbudgeted obligations inherited from prior administrations. That first year of Cortizo borrowing bought the public debt up to a record more than $32 billion as the virus got a grip on us.

The estimates of the economic hit that the epidemic will represent to Panama are necessarily speculative and, in the Panamanian mainstream media, generally spun according to the owners’ political allegiances. Cortizo himself alluded in in July 1 report to the legislature and nation of $2 billion in austerity measures, and boasted of a food assistance program that reached about $1.6 million people, which would be just over one-third of the country’s population. At $80 per month per household, now increased to $100.

The government’s food assistance does not reach much of the population that before the quarantines, curfews and travel restrictions eked out their livings in the myriad pursuits of the informal economy. In any case it’s not enough to feed a family. From many social classes and points on the political spectrum comes the observation that Nito’s economic plan to get us through the epidemic is unsustainable.

A counterpoint demand from the left side of Panama’s labor movement is for a guaranteed monthly family income of $500. But look at the debt. How, other than massive confiscations from all of those who have stolen from the government, grabbed lands both public and privately owned by others, raped the environment via illegal logging, strained Panama’s relations with the rest of the world by money laundering activities or so on, could we pay for this? Neither the dictatorship’s constitution that we have nor the policies of international lenders would allow this. The labor proposal is more realistic for working people than Nito’s program, but without other big changes in Panama and the world is also unsustainable.

Overpriced government purchases, overpaid political apparatchiki and corny information control games make the political problem worse. Reliance on riot cops to keep things under control may be misplaced.

There is and will be a period of class warfare. A nearly closed economy will take away labor’s usual threat of crippling strikes. The debt and the PRD’s minority status will detract from the ruling party’s usual ability to smooth things out with political patronage.

The unpopular PRD figiure who first arose as a dictatorship operative on the University of Panama campus and went on to be mayor of San Miguelito, legislator, housing minister and the PRD candidate who was crushed by Ricardo Martinelli in 2009 may have few chances at a personal political comeback, but nevertheless she’s an astute observer of things and, at the risk of jeers from many sectors, some of the media still call on her to comment. Lately she’s talking about the Cortizo administration reinventing itself and reaching a widely accepted national agreement on the shape of a post-epidemic Panama. She suggests, however, that the current economic orientation will need to change to arrive at any such deal.

Nito, for his part, is open about making mistakes and has repeatedly shown a propensity to change policies that don’t go well. Confrontation and then compromise would be the style of both the president and the labor militants, but the gravity of the economic situation might call for radical measures that one or both sides consider unpalatable.

The Presidencia tweets. Click here to watch the video, which is in Spanish.

Meanwhile, there is this virus with no political preferences

The second wave of coronavirus cases is much worse than the first in Panama. But aside from a little bit of repetition by a few business leaders of anti-scientific memes borrowed form the United States, the anti-mask and “open everything up” stuff seems to be losing out to the doctors’ advice here. Vice President Carrizo’s political base is crumbling on that score as the hospitals overflow.

But despite the spikes in COVID-19 deaths and infections, the global trend is for a reduced death rate for those who do get sick. That’s because, even if neither a promising vaccine nor a specific total cure appear on the horizon, doctors are getting better at treating symptoms.

There is also promising research about how the virus works on a cellular and molecular basis, which may in turn lead to new ways of inhibiting its course of destruction through the human body. A virus for which there is no cure and no vaccine? HIV is one of those, too, but it’s not quite the death sentence that it once was because ways have been found to slow down the infection and treat its symptoms. Some of the better news comes out of the University of California at San Francisco, where researchers have noticed that COVID-19 attacks cells in similar ways that certain cancers do. This, they say, suggests the suppression of the virus’s progress with some of the same sorts of drugs that are use to slow down cancers’ growth. It’s all very preliminary, but around the world many brilliant people are working on many possible avenues to fight the disease. The lack of a vaccine or a “magic bullet” should not be reason for total despair.

Public confidence? Throughout most of this crisis the former health minister, Rosario Turner, was the most trusted figure in the Cortizo administration. There hasn’t been any polling on how her signature on the call for that illegal meeting at Jimmy’s affected that. The then vice minister, Dr. Sucre, was the one who imposed the fines on the PRD and the restaurant, and perhaps he will be the one to regain a measure of trust. The medical profession is traditionally popular in Panama. His problem will be if he gives sound medical advice which is economically impossible to take.

This campus radical, marching down Avenida Central, makes the vice president the focus of her critique. PAT photo from Miss Behania’s Twitter feed.

Contact us by email at fund4thepanamanews@gmail.com

To fend off hackers, organized trolls and other online vandalism, our website comments feature is switched off. Instead, come to our Facebook page to join in the discussion.

These links are interactive — click on the boxes